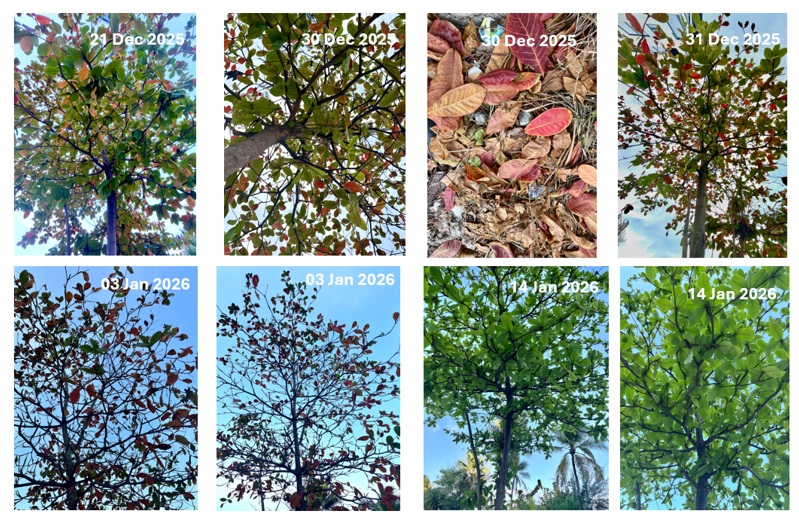

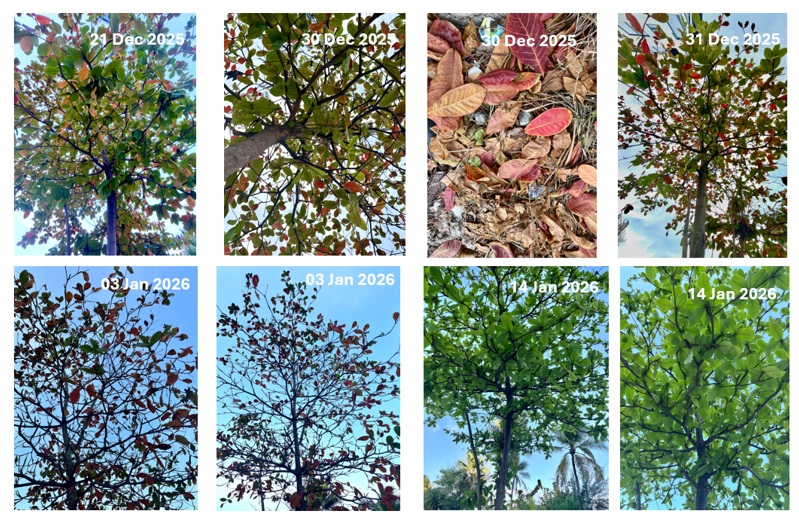

Midhili - The Tropical Almond Trees of Maldives

Midhili; the tropical almond tree, stands quietly along Maldivian shores and island interiors, its w...

When most people think of the Maldives, they picture turquoise lagoons, coral reefs, and coconut palms swaying over sandy islands. What many visitors never see is the quiet network of freshwater wetlands—kulhi and chasbin—where one of the country’s most resilient and culturally cherished crops has been grown for generations: Taro, locally known as “Ala”.

Despite its simple appearance, taro has shaped Maldivian diets, traditions, and agricultural practices for centuries. Today, as climate challenges intensify, this ancient crop is becoming more important than ever.

What Is Taro?

Taro (Colocasia esculenta) is a tropical plant grown primarily for its starchy underground stem, known as the corm. It thrives in warm, humid climates and can grow in wet soils where many other crops fail.

Key features of the taro plant:

• Heart-shaped leaves that can grow over 1 meter tall

• Thick corm that ranges in color from white to light purple

• A fibrous root system capable of anchoring the plant in soft, waterlogged soils

• A mild, earthy flavor once cooked; the raw plant contains calcium oxalate and must be properly boiled or steamed

Both the corm and young leaves are edible, making taro one of the most versatile plants in traditional island diets.

Taro in Maldivian Cuisine: A Cultural Staple

Taro has been a steady, reliable food source for Maldivians for centuries. Even today, where imported rice and flour dominate the kitchen, taro remains a beloved ingredient that connects families to local traditions. Common Maldivian uses include:

How Taro Is Grown in the Maldives

Unlike the terraced paddies of Asia or deep-water systems of the Pacific, taro cultivation in the Maldives has adapted to the unique geography of low-lying coral islands.

1. Cultivation Sites: Wetlands and Depressions

Taro is traditionally planted in small, excavated pits or depressions and inside the Kulhi and Chasbin areas – natural mangroves, marshes or ponds. These areas hold freshwater or at least low-salinity water, allowing the plant to thrive. Islanders often line pits with organic matter—coconut husk, dried leaves, and compost—to hold moisture and elevate soil fertility.

In more recent times, taro is also planted on raised beds or in plastic containers, often as backyard home gardening.

2. Planting Process

• Healthy corm pieces with buds are selected.

• The pits are dug roughly 50–80 cm deep.

• Soil is loosened and enriched with composted material.

• The corm section is planted about 10–15 cm deep.

• Plants are spaced so that leaves have room to spread.

Because fresh water is limited on many islands, taro patches are maintained carefully to avoid saltwater intrusion.

3. Maintenance

• Weeding is essential, as weeds can choke the slow-growing plants.

• Regular water management helps maintain the right moisture level.

• Mulching with coconut fronds reduces evaporation.

Taro patches often become community spaces—places where women and men gather to tend plants, share stories, and pass down knowledge.

Harvesting Taro in Maldivian Tradition

Taro takes 6–12 months to mature, depending on variety and local conditions. Islanders look for signs such as:

• The leaves begin to droop or yellow

• The corm swells visibly at the soil surface

• A firm feel when the soil around the plant is gently pressed

Harvesting is done by hand:

1. The plant is loosened carefully with a wooden stick or hand tool.

2. The entire clump is lifted from the soil.

3. Corms are cleaned, and the mother corm is separated for consumption or replanting.

4. Leaf stalks and roots are sorted—nothing is wasted.

Freshly harvested taro is often cooked the same day, honoring the tradition of sharing the first harvest among family and neighbors.

Why Taro Matters Even More Today

The Maldives faces accelerating challenges from loss of agricultural land due to urbanization and increased infrastructural development, and an extremely heavy dependence on food imports.

Taro stands out as one of the few local crops that can survive in wet, low-lying conditions. Ideally, this should make taro a key component of food security strategies. Taro supports:

• Climate resilience – withstands storms and irregular rainfall

• Local food traditions – keeps culinary heritage alive

• Sustainable farming – grows without chemical inputs

• Community livelihoods – provides income through chips and value-added products

As the Maldives looks toward a more resilient future, revitalizing taro cultivation offers both cultural continuity and practical security.

A Root That Connects Generations

Taro is more than a plant—it is a connection between land and people, the past and the future. By preserving and strengthening taro cultivation, Maldivians would not only be protecting a nutritious and versatile food source but also honoring an agricultural identity that has shaped island life for centuries.

Feb 3, 2026

Jan 1, 2026

Dec 28, 2025

Dec 28, 2025

Nov 10, 2025

Midhili; the tropical almond tree, stands quietly along Maldivian shores and island interiors, its w...

In the far north of the Maldives, Hirimaradhoo faces the planned relocation of its entire community—...

Coral stone once shaped the everyday architecture of the Maldives, forming the walls of homes, mosqu...

Malamathi is an independent, citizen-driven platform that verifies and publishes island and ecosystem data and information from across the Maldives

© 2026 Malamathi. All rights reserved.

Document our Raajje! 🇲🇻