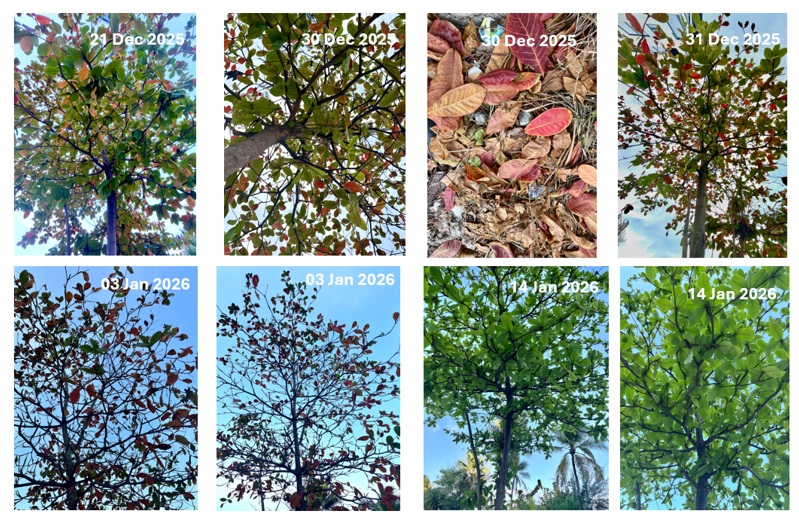

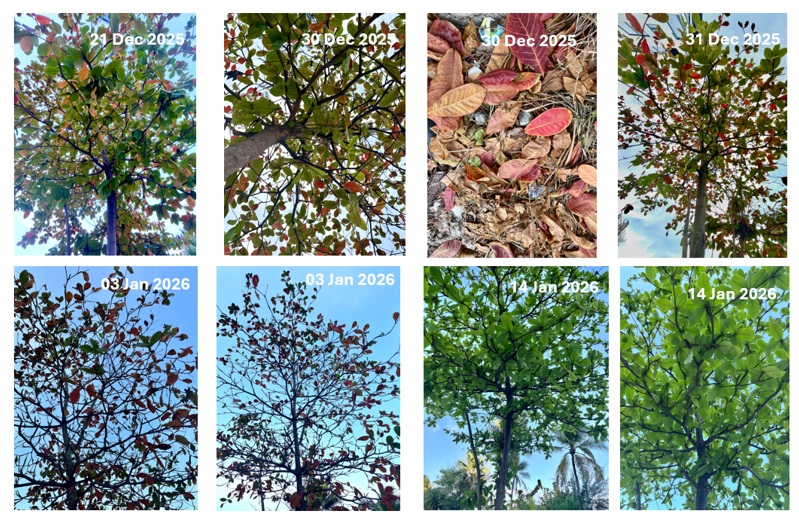

Midhili - The Tropical Almond Trees of Maldives

Midhili; the tropical almond tree, stands quietly along Maldivian shores and island interiors, its w...

I first met Dhon Aisa on a narrow sand path, the kind that curls quietly between coconut palms and screwpines. She sat cross-legged in the sun, peeling apart a bundle of sea-browned fibre with a steady rhythm that made the whole process look effortless. Within minutes, the tangled husk softened into long golden strands — the beginnings of roanu, the coir rope that has shaped Maldivian life for centuries.

For generations, rope-making in the Maldives was more than a craft. It was a skill woven into everyday survival, a livelihood for island families, and a commodity that once carried Maldivian identity into distant shores.

A History Braided With Trade Winds

Long before tourism or motorised boats, Maldivians relied on the coconut palm for nearly everything: food, shelter, mats, thatch, and especially rope. Early trade records from sailors travelling between the Red Sea, India and the Far East mention Maldivian coir rope as exceptionally durable — famed for withstanding saltwater and heavy strain.

For centuries, bundles of roanu left the atolls aboard trading dhonis, eventually reaching ports in India, Ceylon, China, Yemen, and the Persian Gulf.

Coir even became one of the Maldives’ earliest recognised exports. Local histories note that during its peak, coir contributed significantly to island economies, forming part of a barter network long before cash transactions became common.

How Coir Rope Is Made — The Old Island Way

Coir rope making is a patient, almost meditative collaboration between people and the natural resources of the islands.

1. Harvesting the Husks

The process begins with collecting coconut husks — often from mature nuts. The coconut tree, abundant across inhabited islands, is the backbone of the craft.

2. Retting in Seawater or Brackish Mangrove Pits

Husks are soaked for about three weeks in pits dug close to mangroves or in tidal zones.

These pits, fed naturally by seawater, slowly soften the husk, loosening the fibres. Without the right salinity and natural wetlands, the retting process simply wouldn’t work.

3. Beating and Cleaning

After retting, the husks are beaten on logs or flat stones, freeing the fibers. The fibers are washed and left to dry in the sun.

4. Spinning and Twisting

Women — traditionally the backbone of the craft — roll the fibres on their thighs, twisting them into long threads. These threads are then plaited into thicker ropes for boatbuilding, joali (hammocks), housebuilding and fishing.

5. Drying and Bundling

Completed ropes are coiled and sun-dried to strengthen them before use or sale.

Income and Economic Importance

On some islands — most famously Kulhudhuffushi — coir rope making supported hundreds of families. Interviews and local household surveys from the early 2000s show that:

Coir rope was sold locally for household needs, used by boatbuilders, and exported in bundles for international markets where Maldivian coir was valued for its salt resistance.

A Craft Under Threat

Research carried out over the past decade paints a sobering picture.

Studies on coastal habitats, environmental impact assessments, and socioeconomic surveys indicate several threats:

These factors make traditional roanu-making increasingly difficult, and in some islands nearly impossible.

A Thread Worth Saving

Dhon Aisa passed away a few years ago. I realized then and even today, that when she talked to me about her craft, she wasn’t just talking about rope; she was talking about our culture, the labor of our grandmothers’ and mothers, the coconut trees, the lagoons, mangroves and wetlands, as well as the quiet ties that bound island life long before modern industry.

Protecting coir rope making isn’t about preserving a souvenir craft.

It is about honoring an island heritage, safeguarding family incomes, and respecting the natural landscapes that have supported Maldivians for a thousand years.

If those spaces vanish, the sound of hands twisting fiber into rope may fade with them — one more story of the sea lost to time.

Feb 3, 2026

Jan 1, 2026

Dec 28, 2025

Nov 10, 2025

Midhili; the tropical almond tree, stands quietly along Maldivian shores and island interiors, its w...

In the far north of the Maldives, Hirimaradhoo faces the planned relocation of its entire community—...

Coral stone once shaped the everyday architecture of the Maldives, forming the walls of homes, mosqu...

Malamathi is an independent, citizen-driven platform that verifies and publishes island and ecosystem data and information from across the Maldives

© 2026 Malamathi. All rights reserved.

Document our Raajje! 🇲🇻